Friday, December 09, 2005

Thursday, November 10, 2005

I feel compelled to butt in – along with Coppola’s Conversation, I place Nashville somewhere near the top of my list of great American films of the 1970s. I came to this film cold at age nineteen, an Altman virgin, with no love for country & western and total ignorance of Pauline Kael and her cult of geniuses. Franklin cites Henry Gibson’s recording of “200 Years,” a buffoonish bicentennial number that opens the film ("We must be doing something right to last...two-hundred years!"), as one reason the movie’s not a bust. Let’s enumerate some more:

*Lily Tomlin, in her first screen role, plays a gospel singer in a black choir. Lily Tomlin, in her first screen role, plays a gospel singer in a black choir.

*Jeff Goldblum: ghostrider motorcycle hero.

*Shelley Duvall’s “L.A. Joan.” Her lame California grooviness.

*The voluptuous horror of Karen Black.

*Geraldine Chaplin’s patronizing, annoyingly liberal BBC journalist. On watching the black choir: “That rhythm is fantastic. You know, it's funny. You can tell it's come down in the genes through ages and ages and hundreds of years, but it's there. And take off those robes and one is in darkest Africa. I can just see them - naked frenzied bodies dancing in the heat of...do they carry on like that in church?”

*Gwen Welles, the tone-deaf wannabe country singer. Her excruciating naïveté.

*The touch-her-she’ll-faint fragility of Ronnee Blakely’s Loretta Lynnish Barbara Jean.

*The opening credit sequence!

*The voice of Replacement Party candidate Hal Phillip Walker. Ross Perot avant le lettre? His political koans. “When you pay more for an automobile than it cost Columbus to make his first voyage to America, that's politics”.

*The car crash sequence. Brilliantly shot.

If there’s a weakness in the film, it’s Keith Carradine. He just seems so unengaged.

Nashville was released the year I was born, so I don’t have much of a sense of what it felt like to live in 1975 – but I feel that this film most closely approximates what 1975 was like, or rather, what I imagine 1975 to have been like – a sort of post-revolutionary wandering stillness, where events happen but the particularity of those events are inconsequential – where a car crash that holds up traffic for a few hours is as significant as an assassination.

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

Stephanie Young & Juliana Spahr: FOULIPO

Georges Perec, from L'infra-ordinaire: "Make an inventory of your pockets, of your bag. Ask yourself about the provenance, the use, what will become of each of the objects you take out."

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

…In my opinion, formalizing avant-gardes, such as L=A=N=G=u=a=g=e [that was a mistake, but it looks pretty] argue themselves as political due to an allegorical similarity between their poetic practices and some sort of concept of political structure. For example, a Jackson Mac Low poem might be organized in ways that are similar to an anarchist society, in an allegorical sense, just as the Fairy Queen was organized in ways that were similar to a totalitarian monarchy, in an allegorical sense. However, these formalizing avant-garde approaches are really less relevant to politics than topical political writing (agitprop). Agitprop, however, is embarrassing, unless it's funny, so most poetic agitprop seems dated and absurd (like much of Baraka say) and only a little stays good (like mid-to-late Ginsberg (in my opinion)).

And here's the point of critique: old formalist avant-garde work can be turned into professional credentials, whereas old agitprop writing can't. Which seems like a clear sign that the politics of the avant-garde formalist are usually less intended to produce political effects, and more intended to further the artist's reputation, though such works might have a secondary political intention. And I'm okay with secondary political intentions. But, here's the downside, formalizing avant-gardes tend to disdain more direct expressions of political ideology, and it's at the moment when non-allegorized political discourse is rejected by such movements that professionalization is privileged over ideology.

First, if I follow Stan’s reasoning in the first paragraph, this would mean that the poetic practice of the language poets has an allegorical similarity to a political structure. But which political structure? Marxism? If not Marxism, then is it just a general oppositional left critique of consumer culture? If Marxism, how is Rae Armantrout’s Up to Speed, for instance, a Marxian text? I think it would be a mistake to group the poetics and politics of a disparate group of writers such as the language poets under a single umbrella. Maybe some of them simply don’t “argue themselves political”… I realize these are old and much-hashed-out questions, that there’s a rather large discourse around this issue…actually, googling just now, I found some excerpts from a book by George Hartley that ask just these questions, so maybe I’ll drop this line of reasoning. But I want to point out that (shuffling from writing to visual art) El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko, Kazimir Malevich, and the Russian Constructivists were at once formally avant-garde and agitprop, and I don’t think their work is particularly embarrassing or absurd (perhaps dated, but only insofar as any historical avant-garde is dated – as a matter of fact, the pop group Franz Ferdinand uses a Rodchenko-inspired design on their new album cover – now there’s a confusing forest of signs! What would the Archduke think? But perhaps the artist would find it a riot…) Additionally, doesn’t it seem that if agitprop writing cannot be turned into professional credentials the same should be true, perhaps even more so, of radical activity? Angela Davis teaches at UC Santa Cruz, and former Weather Underground members Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn teach at the University of Illinois and Northwestern University, respectively…

Friday, November 04, 2005

This Is Our Only World: A Report on the n/OULIPO Conference, Part 4

The final panel of the n/OULIPO conference was the “Summary Panel”, which included novelist Janet Sarbanes, art historian Johanna Drucker, and poet Tan Lin. Art and poetry critic Carrie Noland moderated. Sarbanes summarized the conference using an “I Remember” constraint, switching mid-talk to an “I Wonder” constraint. It was much more elegant than the rather long summary I’ve composed here, and since you can now read Sarbanes’ piece in its entirety over at Stephanie Young’s blog, I’ll move on to Johanna Drucker’s presentation. Drucker started by reading short poems that seemed to derive from keywords culled from each of the panelists’ talks. She explained that the long history of experimentalism in literature has two cultural traditions we can think about: Romanticism, which tends to the transcendental, and another nameless tradition that resists escape, resists the transcendental. Contra the theorization of much of the 20th century avant-garde, Drucker insists the “experiential” in experimentalism is not an act of liberation. She urges artists and writers to think of their work not as countercultural, but cultural. Drucker tires of the avant-garde and its strict pedanticism, which chides the adventurous artist, “you haven’t performed the avant-garde tradition correctly,” and pulls the artist back to a supposedly “liberating” space. She asked: what will the Oulipo be in 135 years? Her admittedly wicked answer: the seeds of current experimentalism will be muzak played in grocery stores; Perec will be handed out as reading material for kindergartners; in short, the strategies of the Oulipo will be absorbed and integrated into the cultural mainstream, and she looks forward to it.

Tan Lin spoke next, very briefly. As I mentioned before, he spoke of Stephanie Young & Juliana Spahr’s performance in relation to the “dated critical object” and wondered if there was a connection between Oulipian practice and the contemporary practice of sampling. Then something curious happened. Almost off-handedly (I didn’t notice it at first) Lin mentioned the “dematerialization” of the art-object. Johanna Drucker in response insisted that there is no such thing as dematerialization, that dematerialization is a myth. She claimed she had totally “lapsed” and no longer believes in the transcendental or utopian space (there seemed to be some slippage around the axis of terms “transcendental”, “utopian”, and “liberated space” that needed some sussing out). If we say that liberation or utopianism should be a goal in our cultural work, Drucker implied, we condemn ourselves to product-oriented results. Concerning dematerialization, Brian Kim Stefans asked from the audience: what about the data I lost on my computer last week? Drucker: That proves just how material the data was, that it was simply information imbedded on a silicon chip and subject to the laws of the material world. Stefans: what about the artist Vito Acconci and his performance Seedbed, where the artist hid underneath a gallery-wide ramp installed at the Sonnabend Gallery and masturbated while reciting his fantasies about the gallery-goers walking on the ramp above him? Drucker: sounds pretty material to me!

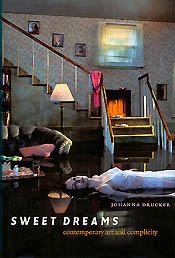

Johanna Drucker, Sweet Dreams:

Contemporary Art and Complicity

I’d like to think about Drucker’s remarks in the context of her latest book, Sweet Dreams: Contemporary Art and Complicity. There Drucker argues that much contemporary art has a complicit relationship with mass-media and the culture-industry, that art (or at least some art) no longer engages in the kind of oppositional critique that has been the hallmark of the avant-garde for the last century and a half, and that critical response to such art has failed to find a language to accommodate such changes. The rhetoric of radicality, says Drucker, has become formulaic and academic; opposition, negative criticality, and esoteric resistance are outmoded:

(Drucker, 49-50)

I must admit I was pretty angry when I first read this. I went to school in the mid-to-late 90s and was taught to think critically about culture; the writings of the

I’ll end on two lighter notes:

Johanna Drucker mentioned that hearing the Rolling Stones’ “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” as muzak in Wal-Mart is the ultimate defamiliarization experience. For members of my generation, however, this is totally familiar. Possibly even expected. “Smells Like Teen Spirit” was turned into muzak less than a year after it was top of the pops.

Paul Fournel said that the Oulipo was not so interested in constraints in the visual arts. I asked Ian Monk anyway whether the Oulipo had any official position on Lars von Trier’s Dogme 95 film movement, which seems influenced by Oulipian techniques. Monk stared into space, deep in memory: “The Celebration. What a terrific film.”

Thursday, November 03, 2005

Wednesday, November 02, 2005

I kept notes diligently during every panel throughout the n/OULIPO conference except one: “The Politics of Constraint.” The speakers were poets Rodrigo Toscano, Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young, and sound-poet Christian Bök. Jen Hofer moderated. There were rumors hours before the panel began that something remarkable was afoot, and any panel with the word “politics” in its title is sure to be interesting, if not necessarily contentious; but the politics panel proved to be the most thought-provoking panel of the entire conference. I stopped taking notes simply because I felt I was missing too much (though ultimately by not taking notes I missed more) and because I wanted to pay close attention to what was being said. Rodrigo Toscano presented first. If you’re at all familiar with Toscano’s work, you’d know that he agrees with the Historical Materialists that “poems act as a barometer of one’s developing social consciousness” and that one of his tasks is to begin to imagine “a new internationally committed political poetry, with enough negativity and critical reflexivity to last into the night.” (Those quotes are taken not from the Oulipo conference, but from a talk [warning: pdf file] he gave at the UPenn “Poetry and Empire” conference in October 2003). I bring these quotes up not only to highlight a facet of Toscano’s poetics, but because I want to read them against something Johanna Drucker mentioned in the summary panel. But I’ll get to that later. For n/OULIPO, Toscano presented an allusive, poetic text that, if I remember correctly, played off the political connotations of the words “constraint” and “restraint”. I remember: “You givin' me lip?”. I remember: “New…lip…oh?” (I’ve asked Toscano to comment on his talk and if he does so I’ll mention it here).* In the meantime, I’ve found an excerpt of the play/poem he read from on Friday night. It was published in the latest Jacket Magazine: “Traux Inimical.”

Six Oulipian Men (facing, l to r: Jean Lescure,

François Le Lionnais, Raymond Queneau; backs

to the camera, l to r: Noël Arnaud, Claude Berge &

Jacques Duchateau

Next, Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young read from a piece they wrote together (they seamlessly read alternating sentences). I noticed something strange right away; at first I thought one of them had a speech impediment, or that Spahr, who had spent some time teaching in Hawai'i, was reading in Hawai’i Creole English, but I quickly figured out that they simply weren’t pronouncing the letter r in the words of their sentences (it almost sounded like Elmer Fudd-speak, or as one audience member put it, baby-talk; so that, for instance, “writer” was continuously pronounced “wite” – a method that made a poignant point in phrases like “the wites of the Oulipo”). Let me be clear: this piece was about many things, and I don’t mean to be reductive or inaccurate, but I’m working not from notes but memory, so what I’m about to relate (like everything I’ve related about the conference) is only fragmentary. Stephanie Young said she may elaborate on her blog, The Well-Nourished Moon. Spahr & Young’s talk frequently made reference to female artists of the 1960s, 70s and 80s who foregrounded the body in their artwork – Carolee Schneeman, Ana Mendieta, Hannah Wilke, Marina Abramovic, Kathy Acker – (and, I may be wrong about this, but if memory serves it was only when Spahr & Young mentioned these artists’ names that the letter r returned and was fully pronounced). They had noticed that several young, usually male writers whose work is influenced by the Oulipo have been able to successfully pass off their work as “radical” or “revolutionary”, while several young, usually female artists whose work is influenced by the body art of the 1970s have had their work dismissed as “old-hat” or “derivative”. Spahr & Young also noted that the Oulipo and the body artists developed their art and strategies during roughly the same era (the 1960s and 70s); the former are often spoken of as a cohesive group even as their individual projects differ, while the latter are rarely spoken of as a group or movement at all. Young & Spahr thus made a case for “carrying the body forward”. At a certain point during their talk, Young & Spahr stopped speaking “live” and a recording came on that continued their essay (complete with the poets alternating their sentences, though I believe during this recording the letter r was pronounced). While the recording projected their voices (disembodied, as it were) the two poets very matter-of-factly undressed. Meanwhile, 2 naked men and 1 naked woman casually walked down the theater aisle, sat down in seats near the front of the theater, and started reading. When Spahr & Young finished undressing they put their clothes back on, undressed once more, and put their clothes back on again. All this was going on as the recording of their text continued to be recited over the theater’s PA system. I believe they repeated this action once more before the piece ended. Content & form had often been debated & discussed during the conference, but this was the only piece that put the tension of those two terms to work viscerally; even as the very important content of their essay demanded close scrutiny, the form (both in the disembodied vocal aspect and the clearly embodied physical aspect) could not be ignored. The fact that such form has been ignored, dismissed, or otherwise rejected by self-described members of the avant-garde was part of the point (Though perhaps the case can be made that the critical reception of the work of 70s body artists has focused too much on form and not enough on content. You're only paying attention to form! You're only paying attention to content! Someone said: Harry Mathews was disappointed when reviewers would pay attention only to the formal logic of Perec's novels and not their beautiful narrative content). Some mentioned that the absent letter r represented the absent female subject. The poet Tan Lin speculated that their performance demonstrated the "dated critical object". Anyway, I’d like to hear from others who were present, or from anyone who cares to amend or correct any mistakes in my account (I’m sure there’s a few and it's obviously not comprehensive). I don’t want to be the only narrator. I’m especially looking forward to anything Stephanie Young may write about this talk/performance, as she hinted she may do. A few other notes regarding Spahr & Young’s talk: in Q&A later that night, Oulipian Ian Monk pointed out that simply not using or pronouncing the letter r in a text does not a constraint make. For it to be a constraint the absent letter r would have had to determine which words were actually used, which didn’t seem to be the case. Monk also referred to their performance as a “strip-tease” (is it possible he’s just ignorant of the body art history referenced by Young & Spahr? at any rate – poor and inconsiderate choice of words), which term, inexplicably, was repeated by summary panelist Tan Lin. One more note: I’ve noticed Los Angeles poet Catherine Daly (who was noticeably absent from the conference – if any local poet should have been invited to be a panelist it’s her) has posted a few thoughts about what kind of performance she might have done. She also contrasts Young & Spahr’s performance with the recent Fence Magazine cover controversy.

Christian Bök presented the final paper for the “Politics of Constraint” panel. The contrast with Young & Spahr’s piece could only have been more exaggerated if Hulk Hogan gave the talk. (That’s actually quite unfair of me – Bök’s talk was terrific, but there seemed to be some unacknowledged questions of gender and performance in what one audience member described as Bök’s “machine-like,” “masculine,” forceful presentation. Said Bök: I saw nothing gendered about my presentation; I was simply reading a straight academic paper in accord with the traditions of the discipline. The audience, in response, laughed in disbelief). Bök, a member of the UbuWeb collective, spoke specifically about the politics of the Oulipo. Or rather the Oulipo’s lack of a coherent political program. Whereas most avant-garde movements throughout the 20th century made politics a central tenet of their respective organizations, the Oulipo, despite its individual members’ left-leaning proclivities, has declined to articulate a politics. The Surrealists – with whom the Oulipo’s founder Raymond Queneau was briefly affiliated – despite their shortcomings, nevertheless managed to sustain a social critique that is absent from the Oulipo charter (my two-cents: this question of the politics of the Surrealists and the perceived lack of Oulipian politics may be elucidated by a reading of Raymond Queneau’s semi-autobiographical novel Odile, wherein the commitment of the Surrealist-like group is portrayed as superficial and opportunistic). The College of ‘Pataphysics, the Oulipo’s immediate precursor, was named as an organization that still retained a certain level of positive political activity. For Bök, whose UbuWeb group is greatly influenced by the Oulipo, the lack of social critique by the Oulipo is a kernel of unrealized potential that still needs to be cracked. Needless to say, the Oulipians present vehemently disagreed. Paul Fournel mentioned an article penned by Jacques Roubaud that explicitly criticizes French Front National leader Jean-Marie Le Pen (using a constraint, of course). Fournel also took issue with the implied political commitment of the College of ‘Pataphysics.

Well I had meant for this to be the final post on the conference, but I think there's enough here to consider for now. I would still like to play those earlier quotes (and others) from Rodrigo Toscano against a few things Johanna Drucker mentioned in the summary panel. Looks like there'll be a Part 4.

*Update: The piece Toscano read at n/OULIPO was called "De-Liberating Freedoms in Transit," an excerpt of which can be found at Silliman's Blog.

Monday, October 31, 2005

First: poet Stephanie Young, who was a participant in the n/OULIPO conference, and whose presentation with Juliana Spahr was one of the most talked-about events of the weekend, has posted an account on her blog The Well-Nourished Moon.

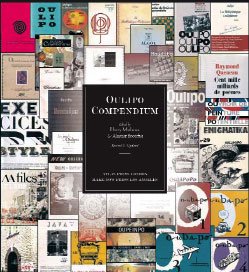

The Oulipo Compendium

available from Make Now Press

Saturday morning the conference resumed with a panel entitled “Words at Work and Words at Play.” The speakers were Bard professor and poet Caroline Bergvall, UCLA professor and poet Haryette Mullen, and Rob Wittig, poet and board member of the Electronic Literature Organization. The moderator was Mady Schutzman. Bergvall presented a fascinating essay on Georges Perec that drew on his “site” writings from Species of Spaces and L’infra-ordinaire. Bergvall suggested that in these works “word play” is jettisoned for “world play”. Perec's interest lies in how the time process of writing and durational performance create new senses of social order by tying writing to contingent social space and time. From Perec’s forward to Species of Spaces: “The subject of this book is not the void exactly, but rather what there is round about or inside it. To start with, then, there isn’t very much: nothingness, the impalpable, the virtually immaterial; extension, the external, what is external to us, what we move about in the midst of, our ambient milieu, the space around us.” In his site writings Perec subjected his writing to spatial conditions: he would write in a particular place for a particular amount of time. Bergvall contends that these sited writings increased his level of engagement by a radical disengagement; by describing a particular time (Thursday 27 February 1969 around 4pm on the Rue Vilin, for example) Perec always at the same time described the deeper social changes occurring in society. Says Bergvall: “Change is the main function of space, disappearance its motive”. These writing techniques go to the source of Perec’s theory of description: why write? When write? Bergvall’s essay played these “site writings” against Perec’s idea of the “infraordinary” (which I understand as the opposite of the “extraordinary” – “the banal, the quotidian, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the infraordinary, the background noise, the habitual”). Can you really capture what you see? This question unsettled Perec. Bergvall also suggested that Perec’s appropriation of Joe Brainard’s I Remember poem deepened the project by combining biographical time with collective time, where memories become shared impressions. Bergvall finally wanted to suggest a possible reading of Perec’s “infraordinary” with Marcel Duchamp’s “infrathin” (infrathin: the heat of a seat just vacated). Where does language go at this level of perception?

Haryette Mullen prefaced her remarks by warning that what she was about to relate would be anecdotal. She wondered about Oulipian themes in her own work (Sleeping With the Dictionary, Muse and Drudge, and S*Perm**K*T among others) and then realized the connection: her initials, H.M., are the same as the famous Oulipian Harry Mathews. Mullen had read Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch and Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler without exactly knowing anything about the Oulipo. She admitted to being more of a Yulipian (not sure about the spelling?) in the manner of jazz master Rahsaan Roland Kirk than an Oulipian. She discovered the literary group only later, and the fact that she uses Oulipian techniques in her own writing is proof that the Oulipo has far-reaching influence. For Mullen, poetry is the ultimate rule-governed writing. Following rules can make poetry more poetic and is proof of the durability of linguistic structures. She credits Oulipian techniques for demystifying poetic inspiration. Constraints and language games are the best ways she has found to get past writer’s block (the problem of the blank page). Textual transformation and language games are like a return to Lewis Carroll and the delight one finds in the clutches of the Jabberwock.

Rob Wittig began his talk by claiming Psychology as the master-discourse: one can understand American politics by asking the simple question, “What kind of dad do I want?” Oulipo engages in play, and play for Wittig is a state of mind. But what is the payoff for constraint? First, it is process-help for the miserable chore of writing. The well-known quote “writers think they hate writing but they only hate the first few minutes” rings true for Wittig, and using constraints can help a writer begin his or her arduous task (once again, the problem of the blank page). (An aside: Paul Fournel suggested that it is very easy to write during those first few minutes; simply write a sentence such as "After dinner I took a stroll through the beautiful city of New --", leave off in mid-sentence, go to sleep, wake up the next morning, and simply begin writing where you left off "--Orleans"). Second, it’s simply fun to be involved in a game. Third, the results of constrained writing often offer a sense of craft as proof of the ordeal of writing, the long pull from the red to the black, where rhymes are earned or suffered in the troubadour tradition. Wittig also spoke of constrained writing as palliative for emotional distress and a tool for the ordering of intentions. "The horror of having one’s mind in a mêlée." Oulipian constraint can be seen as the ultimate rebuke to Romanticism. Georges Perec once sat in a café and watched a romantic diner eat and write. Perec’s description of the diner: “a mouthful, a concept, a mouthful, a concept, a mouthful, a concept…” Wittig ended by placing the pranksters from the Church of the Sub Genius in the Oulipian tradition and mentioned a possible intervention into everyday life we all could make. Buy a parrot and teach it to say the following words: “I understand what I’m saying. I’m being held against my will. Help me.”

The second panel of the day “Science & Chance: Aleatorics vs. Automization” included poet Bernadette Mayer, Matias Viegener, and Oulipian Ian Monk. Maggie Nelson moderated. My Mayer notes are fragmented – she has a compelling personality that makes you want to just sit and listen to her talk and laugh – so I will try to make some sort of sense. Mayer shares with the Oulipo an obsession with language and hilarity. She asks: does Chance need to be exonerated? One thing she likes to do is write poems using the first and last sentences of trashy novels (she read about a dozen of these and they were uproarious). Mayer said: “If Chance were sitting at a table I would have dinner with it. Perhaps it would order a good wine. I can’t tell.” She mentioned her story “Story” as a possible Oulipian-esque text (a description of the story from The Bernadette Mayer Reader says: “'Story' is a novella-length work in which stories interweave in a diamond-shaped structure so that at its center fourteen stories are going on simultaneously. Each section is given a title that is a form of storytelling”). Mayer said she never has anything to say in the ordinary literary sense so she uses “time” as a theme or constraint in much of her work.

Matias Viegener again began his talk by invoking the Ben Marcus vs. Jonathan Franzen essay in the September issue of Harper’s. For the most part, said Viegener, Marcus resists reducing the argument to experimentalists vs. realists. However, Marcus lacks a clear definition of the “experimental”. If narrative realism, to quote Carla Harryman, is an “addiction to transparency”, what pray tell is the experimental? The experimental is usually not used in the strict historical sense by current writers . Unlike “postmodernism” or “deconstruction” says Viegener, the term “experimental” is never used to sell things. (I take a bit of an issue with this – concept cars are usually called “experimental” and are used by auto design firms to sell ideas; novels too are sometimes marketed as “experimental”). The historical avant-garde is usually linked to manifestoes, which are programmatic rather than experimental. And the most successful literary experiments are often very simple (e.g. Joe Brainard’s I Remember; but there was some mumbling by the audience that I Remember isn't exactly experimental). Viegener then outlined the scientific history of “experimentalism” from Aristotle through Francis Bacon and the Enlightenment to the present (I will not go into detail here; I am too ignorant of scientific history and would tremble with inaccuracies). The Oulipo, after taking note of the early and mid-20th century avant-gardes, chose instead to disavow “literary experiment” for “literary potential.” Then Viegener suggested 2 literary models for “experimental potential”: the first was a psychologist I had never heard of (Menan or Mynan or Meinan? If anybody knows for sure, please comment or let me know otherwise).* The second was Gilles Deleuze who “makes it possible to talk about the new without blushing, and generally rejects genre and avant-gardes.” If narrative realism is reactive (and that’s a big if), literary experiment is active. Some other notes from his talk: constraint cannot be rigid; it must creak (this is in reference to the clinamen, a deviation from the strict consequences of the constraint, according to the Oulipo Compendium – for instance, the one place in a "novel without adjectives" where an adjective is used). Finally, Viegener suggested that to describe experimental writing as marginal or difficult diminishes the work’s power and its potential pleasure for readers. From the audience, Vanessa Place pointed out that narrative realism is often subject to experimentalism itself; Zola wrote The Experimental Novel, where experimental = experience. Michael Silverblatt, also in the audience, prefaced his remarks by warning that what he was about to suggest was unfashionable and sentimental. Isn’t the reason we’re all here, asked Silverblatt, isn’t the reason we’re all still interested in the Oulipo explicitly due to the fact that the group included three geniuses (Perec, Calvino, and Cortázar – the last of whom was actually not in the Oulipo but was a member of the College of ‘Pataphysics) and produced three masterpieces of 20th century literature (Life: A Users Manual, If on a winter’s night a traveler, and Hopscotch). Needless to say the appeal to masterworks did not go over well (in private conversation several writers told me that there are ways to measure a work’s success without resorting to the “masterwork” tag), except with the Oulipians, who insisted: “There will be more! There will be more!”

Funny, I’m writing this in Microsoft Word and it wants to auto-correct “clinamen” as “Klansmen”.

Part 3, which I hope will be the final installment, will cover the final 2 panels from the conference, including the electric panel on “politics and constraint.”

*UPDATE: Matias Viegener writes to say that, besides Gilles Deleuze, the other literary model for "experimental potential" is Alexius Meinong, an Austrian philosopher, phenomenologist and experimental psychologist.

The Los Angeles Oulipo conference (or n/Oulipo or noulipo as others have it) is over. Its participants and audience must now get back to the book (or paper or writing or internet or nature as the case may be). I thought about using a constraint to compile these notes but it seemed both too obvious and too taxing. I have enough trouble updating “me old blog” as it is – I haven’t stretched enough to jump another hurdle. Maybe a few laps around the track will tip me into shape. I apologize in advance for any lacunae, inaccuracies, reductions or misinterpretations in what follows. I also apologize for the stilted prose. I’m working from notes, some of which seem incoherent now, and I’ve had very little sleep the past few days. Conversation went deep into the night. I’ve included very little of my own thoughts and reactions to the work presented. I hope instead to offer a summary of the event (though I suppose the title of this blog-entry and what I choose to note and ignore reveal my own interests and biases). When the yearbook is published next year you will be able to read some of the essays, poems, and prose that were presented at the conference. Last year’s edition (from the Séance conference) is freshly printed from Make Now Press and should soon be available here.

CalArts professor Matias Viegener opened the proceedings by invoking the infamous Ben Marcus essay on experimentalism and realism in September’s issue of Harper’s, “Why Experimental Fiction Threatens to Destroy Publishing, Jonathan Franzen and Life as We Know It” (an excerpt of which can be found here). Viegener suggested that the essay is too defensive and does not go far enough in its interrogation of the conflict between experimentalism and realism. The essay’s primary fault is that it offers no real definition of the experimental. On the other hand, it does open a potential space for the discussion of the experimental inclination in writing. It was from this space that Viegener hoped the n/Oulipo conference would operate.

Paul Fournel, President of the Oulipo (or King of the Umpa Lumpas, as others had it) gave the next address, dedicated to recently departed Oulipian Jean Lescure. Fournel described how Raymond Queneau recruited him in the early 1960s “as a slave” for the newly formed group (but, he added, “everybody loves Raymond”) and that they created “a secret garden of research and friendship”. They were interested in the non-immanence of constraint and math & science as structural elements of textual production. Fournel carefully differentiated constraint from structure. Structure is focused on the text while constraint is focused on production (this distinction was brought up frequently during the conference). Constraints, he said, can be found in numerous “anticipatory plagiarists”. Constraints for the Oulipo have a pedagogical efficiency and can be exclusively related to the writer of the text and not just the text itself.

The first panel was entitled “Letters and Numbers” and included Brian Kim Stefans, Christine Wertheim, and moderator Douglas Kearney. Stefans asked: “What can the Oulipo do for new media?” To be honest, Stefans read so quickly that I didn’t manage to write much down or follow everything he said, but here’s what I have: words are traditionally privileged entities; but words are not just another element to be used like sound or color. Stefans is interested in digital works for which texts solve a problem. He suggests that the limitations of media art form a kind of constraint. As he read his essay he projected images from various works of media art on a screen behind him. Those interested should explore his fascinating website arras.net for links to some of these new media artworks (or his blog Free Space Comix). And be sure to check out his work as well (his book Fashionable Noise: On Digital Poetics goes into many of his ideas in-depth). Christine Wertheim, a member of the Institute for Figuring, presented an intriguing and complex essay that seemed to parody scientific inquiry by employing a pseudo-scientific theory she developed herself. Integral to her theory is the interactivity of the (textual?) body and the symbolic. For Wertheim, language is a visual phenomenon. Structures found in nature and mathematics can be applied to an analysis of language due to “knots” or “nots” in space-time. For Wertheim, the universe is “linguistico-conceptual”. To prove her theory she projected slides that combined mathematical equations with visual poetry. We all know that the substance of the universe is space-time, but for Wertheim the substance of the linguistic-universe is “time-space”. Through visual-poetic alchemy (“time-space” converted to “+/’me --> rhythm” and further series of playful metamorphoses of linguistic characters) Wertheim showed that language could be smelted into seven Aristotelian categories (I couldn’t catch all the categories because she changed the slide after only a few moments). This was proof that ideology, i.e. binary categories of conceptual thought, is embedded in language itself (and as students of Western Civilization we all know that binary opposition is one of the ideologies at the basis of human thought). Wertheim ended her talk by urging us to move beyond simple binary opposition.

British Oulipian Ian Monk gave the next address on “what the Oulipo is not”. According to Monk, the Oulipo is not dead, but it might smell funny. The Oulipo does not seek to suggest what one must do; it seeks to say what one can do (if one wants to do it). If you write a novel without using Oulipian constraints, the Oulipo will not say, “yes, this is all nice and good, but you’ve used all the letters in the alphabet here.” The Oulipo ultimately seeks to solve the problem of the blank page. Monk prefers to use the terms “structure, form and technique” rather than “constraint.” By using techniques, you will get something other than a blank page – that something might be crap, but it’s something. And ultimately it is up to the writer whether he or she wants to use techniques or not. On the question of the translation of Oulipian texts, Monk says that it is essential that the translator retain the formal technique in the translation. An audience member asked Monk to describe an Oulipian meeting. Monk said, first, that each meeting must have at least one new creation or text. Secondly, there must be a “rumination” (an idea for a new creation). Next, usually during supper, the Oulipians engage in “erudition” (that is, they present to each other various interesting texts and works that they have discovered –other novels or poems that may use Oulipian techniques). Finally they all pay up for dinner, usually $10. As Monk explains it, some Oulipians have a great deal of money, some less, so they all try to pitch in the same modest amount. Monk ended with some threatening advice: if you ask to be a member of the Oulipo, you will not be a member of the Oulipo.

The next panel, “The Contents of Constraint,” consisted of Paul Fournel (again), Oulipo-esque novelist and poet Doug Nufer (who has a great day time job – he runs a wine shop in Seattle) and Vanessa Place, who has a new novel out called Dies: A Sentence (the entire 117 page novel is a single sentence). Place presented an allusive essay I would much rather have read, its density defeating my patience. My one note from her talk: the question of form is exhausted. Fournel limited his remarks to the topic of constraint, which “forces language to speak that which it does not want to speak.” Sometimes constraint is totally obvious (e.g. Perec’s La Disparition, a novel composed without the letter e). When constraint is not obvious, the constraint is usually more complicated. Concerning the politics of revelation: if the constraint can be re-used by others, the Oulipo recommends that it should be revealed. But under what conditions would one not wish to reveal a constraint (“Mathew’s algorithm,” for instance, is an unknown constraint Harry Mathews used to compose Cigarettes)? First, there may be commercial reasons. Often readers may be turned off if they are told a book has been written using constraints. Second, there may be a personal, secret reason (the case of Harry Mathews – he simply didn’t want to tell anybody). Third, by not revealing the constraint a writer can focus the attention of critics on another aspect of the work, such as plot or character. A French critic once reviewed Perec’s La Disparition without noticing there was no letter e. Italo Calvino was afraid to reveal his constraint for If on a winter’s night a traveler… because he worried it might scare readers away. But revealing, said Fournel, can be another way of hiding. Surrealist automatic writing often reveals constraints that do not look like the freedom it purports to access. Doug Nufer then addressed the old saw of "form & content". In commercial fiction, he noted, form and content is not an issue. Imagine how much more interesting Richard Ford’s The Sportswriter or Annie Proulx’s The Shipping News would have been if they had been written in the forms their titles reference. Ultimately, commercial fiction is defined by arbitrariness and is ruled by a dictatorship of taste. Purveyors of the conceit of “taste” often fail to recognize parody. Witness the genius of National Lampoon’s 1964 High School Yearbook. For Nufer, form is content. Constraint creates content and content creates restraint. Nufer then related an anecdote that illuminated the question of the revelation of constraint. Nufer was employed teaching literature to prison inmates. As part of the program the prisoners read his book Never Again (a 200 page novel in which no word is repeated).* The prisoners very earnestly and respectfully told Nufer that they did not like his book. But when the prisoners were informed of the formal constraint they became very interested and insisted on reading the book again.

The evening readings: Janet Sarbanes read from a novel about the president’s daughter; Bernadette Mayer read some hilarious n+7 poems (the source texts of which seemed to be sexual instruction manuals); Vanessa Place read from her novel Dies: A Sentence; Christine Wertheim read some visual poetry (which, she explained, was meant to be looked at and not necessarily read); Doug Nufer read some Oulipian-inspired work and sang a tin pan alley song (I believe it was a poem sung backwards); Rob Wittig read some Google poems; Tan Lin read from an unpublished novel (for a more detailed account of Tan’s reading check out Stan Apps at Refried Oracle Phone); and Rodrigo Toscano (along with Christian Bök, Stephanie Young and Brian Kim Stefans, all of whom I was happy to finally meet) read from a play (I didn’t catch the title) which was definitely the highlight of the night.

Okay, I’ve gone on long enough, and probably longer than I ever have before. If you attended the conference and wish to add anything or correct my mistakes or clarify any misunderstandings, please comment. And check back soon for Part 2.

*CORRECTIONS: Doug Nufer sends word that the book he had the prisoners read was not Never Again, but Negativeland (where each sentence has a negative construction). Also, and I can't believe I didn't recognize this, the song Nufer sang was "Star Dust" with the lyrics rearranged by spoonerism and inversion.

Tuesday, October 25, 2005

The end of October: my favorite time of year. Mischief making, arriving rains, and (in

Thursday, October 13, 2005

Wednesday, October 12, 2005

Saturday, October 08, 2005

Noulipo: Experimental Writing Conference

Sunday, October 02, 2005

~~~

Did you know that our solar system's tenth planet has been named Xena? And that its moon is Gabrielle? Is this what happens when pop culture replaces Western culture in the popular imagination? How many people really know or care about the trials and tribulations of Ulysses or Madea, as opposed to, say, the latest mystery Locke, Jack, and Freckles conjured up last week on Lost? Will future constellations be called Cosby or Fonzarelli? Is that the monster that lies beyond the depths of Hades and its ruler Pluto? Xena: Warrior Princess?

~~~

Saw Cronenberg's new film, A History of Violence. Very subtle for this director, but he still managed to make the audience uncomfortable (yes, I have a magic ability to guage audience reaction; actually I just listen closely to their comments walking out of the theater). Annoyed that someone would bring a group of five kids aged about 2-10 to the late show on a Friday night; a movie with pretty explicit sex and violence to boot, including a wonderful cunnulingus scene. I won't say much about the plot other than that the title is a red herring. It's not the violence but the sex you should pay attention to.

~~~

At the film mentioned above, screened in Pasadena, caught the trailer for Ang Lee's new gay cowboy movie with Jake Gyllenhaal-Heath Ledger getting it on, Brokeback Mountain. The audience did not respond kindly: uncomfortable laughter, cat-calls. Someone yelled out: "Hell no! Hell no!" Did I fall asleep and wake up in a red-state?

~~~

New at the top of my "must-be-restored-and-released-on-dvd" films: Jacques Rivette's Celine & Julie Go Boating. Tedious at times, but then again, the next morning...

Friday, September 02, 2005

New Orleans, Louisiana and the Mississippi Gulf Coast

August 29-September 2, 2005

It's like 'yeah, yeah another hurricane.'

It's like a roller coaster.

It's like sitting on needles.

It’s like a train coming and we can’t get out of the way.

It's like a skater who pulls himself to his own center, spinning faster and faster.

It's like opening the gates of hell.

It's like a fear orgasm.

It's like a big room and we were lucky in that sense.

It's like a ghost town.

It's like I've been there before.

It's like we're feeling our way through.

It's like the whole time I was on input remembering things that might not be there next year.

It's like our little tsunami.

It’s like a favorite uncle.

It's like having the only gallon of milk where there is four feet of snow.

It’s like cereal in a bowl.

It's like filling a bucket up with water.

It's like filling up an ice cube tray.

It’s like a city in an earthen bathtub.

It's like every possible scenario of not good.

It's like watching not only your life, but the lives of everything you've ever been involved in, just floating away.

It's like a young lion moving away from the pack.

It’s like watching an action movie.

It's like a scene from Mad Max in there.

It’s like the Grinch Who Stole Christmas.

It's like they're people right out of a horror movie.

It’s like the walking dead.

It's like what you see on TV and never thought would happen to us.

It's like watching one of those special effects loaded Hollywood disaster movies.

It's like 9/11.

It's like it was hit by a bomb.

It’s like Hiroshima.

It’s like World War-whatever-you-want-to-call-it.

It's like genocide, a modern type of genocide.

It’s like the worst nightmare of the worst nightmare.

It’s like anarchy.

It's like being kicked out of school, being fired from your job, and having your apartment burn down all in the same day, and then not even knowing if that's the case or not.

It's like living in a tent in the middle of the woods.

It's like going into the desert and starting from scratch.

It's like a chapter of our life is erased.

It's like sitting on the bench in a football game, only 11 guys can play and we're waiting to get in the game.

It's like a hand on the top of the head of a drowning man pushing him farther under.

It's like a very strange vacation.

It's like someone stabbed you in your heart.

It's like a big get together.

It’s like being in a third world country.

It's like Mogadishu out there.

It’s like downtown Baghdad.

It's like seeing something very sacred to you violated and there's nothing you can do about it.

It's like it's following us.

It's like a big sauna here.

It's like devastating times a hundred.

It's like a tourniquet on the entire country.

It's like going to a ballgame for a month, because where are you going to go?

It's like they're in a battlefield and have no idea what the hell is going on on the other side.

It's like the difference between being run over by an 18-wheeler and a freight train.

It's like living on an island.

It's like dropping into a black hole.

It’s like black people are marked.

It's like they're punishing us.

It’s like the death of a friend.

It's like losing a family member.

It's like going to a football game but then you don't go home.

It looks like a flea market.

It’s like they’ve never been to a hurricane before.

It's like it's at your fingertips, if you just stretch out your arm, but you can't do it.

It's like a big soup bowl.

It's like I'm sitting in a dream.

It's like civilization gave up and moved away.

It's like I'm there and I'm feeling it.

It’s like toxic gumbo.

It’s like an injury that you can't control.

It's like peeling back the layers of an onion.

It's like dropping your car into a swimming pool while it's still running.

It's like we're fighting a war in another country.

It's like your whole life, just in one storm, totally nothing, you just got to start over.

It's like the boy who cried wolf.

It's like another place, some waterlogged cousin of the city I once knew.

It's like the entire Gulf Coast was obliterated by the worst type of weapon you can imagine.

It's like seeing something very scary to you, and there's nothing you can do about it.

It's like the city of Atlantis.

It's like watching your child harm himself or being harmed and since they are an adult, there is nothing you can do.

It's like the L.A. riots except you've got nowhere to run to and no one to respond.

It's like when you lose your purse, and at first you think, 'Oh, my wallet,” but then you keep remembering more and more stuff you wish you hadn't lost: 'Oh, those earrings my grandmother gave me. Oh, that credit card receipt that I need.'

It’s like a bad fairy tale.

It's like the death of your life, you know?

It's like a defensive back being burned.

It’s like the picture of Dorian Gray which has been hidden in the attic.

It was like trying to lasso an octopus.

We are like little birds with our mouths open and you don't have to be very smart to know where to drop the worm.

They're housing us like animals.

We are like pure animals.

Tuesday, August 30, 2005

Jia Zhang Ke’s The World, a realist rendering of contemporary Beijing youth, and Wong Kar Wai’s 2046, a romantic phantasia of late 1960s Hong Kong, stand at two distinct points on the aesthetic field of new Asian cinema. While both might be considered “art films” (with all the accolades and approbation the term implies) they couldn’t be more different in execution and affect. The World, like Jia’s previous films Unknown Pleasures and Platform, records an excessively present world, where time seems to have no future and the past is something that is only implied. 2046, on the other hand, manically tries to recapture a lost past (though not, I think, in a Proustian sense; memory in À la recherche du temps perdu is for the most part involuntary, whereas Wong’s characters recount and embellish their pasts voluntarily, even and especially when they try to escape their pasts). In 2046 only the past and future are represented on screen. The present is just a voice. The World in contrast is emphatically present, and proceeds in long, medium-shot takes that have come to typify they style of certain Asian filmmakers (one wouldn’t want to call them a school, for the style can be traced across cultures, from Hou Hsiao-hsien and Tsai Ming-liang to Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Shinji Aoyama…and perhaps even further afield to Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and Nuri Bilge Ceylan). Single shots may last several minutes or more, with only the most minimal of movements taking place on the margins of the screen. Audience tolerance for this style can be very low. Several couples walked out of The World at my screening when certain scenes passed the minute mark with little or no dialogue. I find the languors rewarding, however, and view them as a generous invitation from the filmmaker to think about what we’re seeing and hearing, to trace the associations and ideas presented throughout the film, as opposed to the immediate reaction demanded from most mainstream cinema. My thought processes are so heightened during Jia’s films that leaving the theater and going outside into the real world seems like embarking on a long nap. 2046 is just as demanding, though it doesn’t ask the viewer to swim in the lake of long takes; rather, its asks that the viewer walk along a slowly-developing narrative path full of detours, backtracks, and imagined futures. Though many scenes in 2046 are certainly long, Wong employs a colorful, rich, mind-meltingly beautiful cinematography (thank you, Christopher Doyle – your cinematography moves me) that is something akin to liquid cinema. The effect is almost the opposite of The World’s: when the film ends (I’ve seen it twice now) I feel that I’ve awakened from a long, inspiring dream. These two films, so different in style and method, serve as a slap to the face of mainstream cinema’s universal cretinization*.

I’ve heard many critics claim that since The World is the first of Jia’s films to receive distribution in mainland

Thursday, August 25, 2005

Wednesday, August 24, 2005

UPDATE: Fascicle isn't live yet, so I've taken away the link to content. Will restore in time.

Isabel Nathaniel's "The Beholder: A Tale" is given its own heading in the TOC, "short story in verse." If I'd noticed that distinction before I started reading the piece, I might not have been so irritated with its first three sections, which are tedious short story scene-setting.

But tedious short story scene-setting is tedious even in short stories, no? Why should it be less irritating simply because the form is a short-story-in-verse rather than a poem? Or if you're still irritated by the piece, only less so than if it were a poem, where does the reduction in irritation lie?

UPDATE: Jordan responds, fairly.

Saturday, August 20, 2005

Mother: The West Side, that's where we live. Do you know where Hollywood is?

Boy: The North?

Mother: No, Hollywood is the East Side.

Yeah, well, I guess Hollywood is on the East Side if you live in Santa Monica. I've always thought of it as central. But if Hollywood is on the East Side, what's downtown, or East L.A.? Or Whittier?

Also pleased that the plot of Sunset Boulevard is set in motion in a manner true to Angeleno life: Joe Gillis doesn't want to lose access to his car. Thom Andersen must have made this point in Los Angeles Plays Itself, no? I can't remember. I only remember Jack Nicholson's Jake Gittes in Chinatown (hmmm...Jake Gittes...Joe Gillis) described as "castrated" because he has no wheels.

I was flabbergasted to see the names Erich von Stroheim, Cecil B. Demille, Hedda Hopper, and Buster Keaton flash onscreen during opening credits to Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, which surprisingly, stupidly, along with Double Indemnity, I had never seen before last night (American films of the 1930s through 50s, noirs especially, are a blind spot in my film knowledge). Why have I avoided seeing these films for so long? I was instantly enraptured. Watching them, I felt little pieces of cinema history and pop culture fall into place (Oh! So that’s where “I’m ready for my close-up now, Mr. Demille” comes from…Mulholland Drive makes so much more sense to me now…Barton Keyes…Barton Fink). It was the same feeling I had a few years ago hearing a fairly decent Beatles tune I had somehow never heard before ("Hey Bullfrog"). The mix of comedy and suspense in Sunset is masterful. With every line and every scene my jaw dropped a little lower. That there was a monkey-in-the-coffin bit was especially delightful. Double Indemnity, more straight noir, was also excellent, though I was initially disappointed to see the same story flashback structure used in both films. I suppose these films are old hat for most filmgoers, so please excuse my excitement, and slap me for my negligence.

I was flabbergasted to see the names Erich von Stroheim, Cecil B. Demille, Hedda Hopper, and Buster Keaton flash onscreen during opening credits to Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, which surprisingly, stupidly, along with Double Indemnity, I had never seen before last night (American films of the 1930s through 50s, noirs especially, are a blind spot in my film knowledge). Why have I avoided seeing these films for so long? I was instantly enraptured. Watching them, I felt little pieces of cinema history and pop culture fall into place (Oh! So that’s where “I’m ready for my close-up now, Mr. Demille” comes from…Mulholland Drive makes so much more sense to me now…Barton Keyes…Barton Fink). It was the same feeling I had a few years ago hearing a fairly decent Beatles tune I had somehow never heard before ("Hey Bullfrog"). The mix of comedy and suspense in Sunset is masterful. With every line and every scene my jaw dropped a little lower. That there was a monkey-in-the-coffin bit was especially delightful. Double Indemnity, more straight noir, was also excellent, though I was initially disappointed to see the same story flashback structure used in both films. I suppose these films are old hat for most filmgoers, so please excuse my excitement, and slap me for my negligence.

Thursday, August 18, 2005

Wednesday, August 17, 2005

Monday, August 15, 2005

Poet Jen Hofer (“like offer, not like gopher”) was kind enough to open her home Friday night to the Angeleno rabble by hosting and co-curating , with filmmaker David Gatten, an evening of cinema & poetry entitled The Moving Word.

The evening began with a film by Janie Geiser, followed by Will Alexander reading from his latest book, Exobiology as Goddess. There were also films by Paolo Davanzo (who runs the Echo Park Film Center), David Gatten, Adele Horne, Lewis Klahr (with music by Rhys Chatham), Lisa Marr, and Lee Anne Schmitt, as well as readings by Haryette Mullen, Jane Sprague, Diane Ward, and Jen Hofer. Quite a lot to take in, and I didn’t even mention the pre-show impromptu musical performances (a group of people, I don’t know who, played incredible old-timey country & bluegrass music, two guitars & a fiddle). Sorry I don’t have specifics, I didn’t take notes. Jane Sprague read from “White Footed Mouse, Field Notes” which you can read online in a PDF document of the journal ecopoetics no. 3.

Also got to talk a bit with Ara Shirinyan, and finally got to meet Stan Apps & Mathew Timmons (at least I think it was M. Timmons...I didn't catch the last name, correct me if I'm wrong).

Oh yeah, I joined the Totally Obvious blog and will be posting there occasionally.

Wednesday, July 20, 2005

Friday, July 15, 2005

My city worries me. The iconic, Disney-sponsored,

"He's provocative, he's controversial and unafraid," they say. "He is a visionary, and he needs to execute that."

Moving sideways, Mike Davis describes one possible future for

Be sure to check out the artificial archipelago of The World and the future tallest building in the world, Burj Dubai.

Thursday, July 07, 2005

All plots tend to move deathward. This is the nature of plots. Political plots, terrorist plots, lovers’ plots, narrative plots, plots that are part of children’s games. We edge nearer death every time we plot. It is like a contract that all must sign, the plotters as well as those who are the targets of the plot.

And rise this morning to the terrible news from London. What comes next?

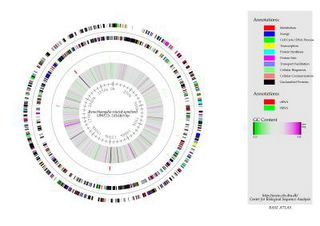

Genome Circle Plots

Meanwhile, googling “murderous innovation” (don’t ask) I come across strange gambling pages strung with oddly compelling phrases like, “A global cager rejoices” and “sometimes a cowgirl related to The Parisian hibernates” and “the harpullia is incontestable”. Who is the Parisian?

I believe these are spam pages filled with nonsense sentences designed to attract wayward searchers like myself. Though I could be wrong.

Elsewhere, Jane Dark analyzes the chilling picture of the day.

~ ~ ~

Candyland : Big

as

A) NAFTA : The

B) Ray Harryhausen : 9/11

C) Benny Hill : Romeo Montague

D) Mark David Chapman : Captain Ahab

Friday, July 01, 2005

A long final chapter on literature proclaims its superiority over all other arts. It is the only one capable of reasoning and the only one that can ‘criticise itself’ or indeed criticise anything; it is also the only art capable of moralising.

Is this true? Granted, I haven't read the book, and this paraphrase may depend on missing context, but as it stands it seems outrageously false. Most visual art from the post-war period to the present has been engaged in an ongoing critique of its own practices and assumptions (viz. minimalism, institutional critique, conceptual art), and one could make a case that Jean-Luc Godard's entire oeuvre is critical of other films as well as the medium of film itself.

Thursday, June 30, 2005

Wednesday, June 29, 2005

Judging by the King Tutankhamun exhibit at LACMA, I'd have to say, ehhhh. Woke up at about 5am to get in line. This must be the first museum show I've ever seen that's sold and structured just like a ride at Disneyland. The wait in line is about 2 hours. While in line, you gape at the people, engage in small talk, or munch on the free Krispy Kremes supplied by the museum. Every once in awhile, as you creep forward, you pass fake Egyptian columns or statues made of plaster. When you finally reach the end of the line, you and 50 other souls gather in a tiny room, the doors close around you (locked in! Just like Disney's Haunted Mansion ride!) and a short video narrated by Omar Sharif plays on widescreen tv. When it's over, a door mysteriously opens, and an illuminated bust of Tut awaits.

The conversation you hear at large-scale museum shows is a swamp of disinformation and honest naïveté ("Tut must have payed a lot of money for the workers he hired to make these artifacts" or "Why'd they raid his tomb, anyway?"). The show itself? Perhaps it's a bit post-modern of me, but I've seen so many fake Egyptian artifacts, good reproductions apparently, that the real things carried no aura for me. The fake stuff you see while standing in line doesn't help in this regard. I turned a corner in the show and saw a huge, beautiful bust of an Egyptian god, sure that it was another prop. (I'm reminded of Dylan's song Isis, "I broke into the tomb, but the casket was empty. There was no jewels, no nothin'! I felt I'd been had"). There were, however, a few wonderful pieces that rekindled my childhood dream of being an archaeologist (I only wanted to be an archaeologist of the 20s or 30s, fighting fascists and swinging from whips). An intricately carved child's chair, giant model ships, golden statues of falcon-headed Horus, gold necklaces ("I was thinkin' about turquoise, I was thinkin' about gold, I was thinkin' about diamonds and the world's biggest necklace"). The biggest disappointment, though, was that the iconic pieces you think about when you think about Tut (the golden death-mask and coffin) were nowhere to be found. They were too expensive to insure for travel to the United States.

Friday, June 17, 2005

I remember my freshman year of college when Professor Earl Jackson, Jr. read some excerpts from Frisk in class and a preppy girl sitting next to me scrawled in her notebook, "Note: avoid Dennis Cooper."

It would be great if other writers associated with the New Narrative would start blogging. Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian would be excellent bloggers, addictive reads. I've read some of Killian's blog-like entries on the Poetics List and he's a natural.

Thursday, June 16, 2005

Thursday, May 05, 2005

Thursday, April 21, 2005

from Living Room by Michael Snow

Snow also screened See You Later/Au Revoir, and The Living Room, the latter notable for using digital effects now common in many

I’ll leave Franklin to describe the Tony Conrad films; aside from the footage of a young Mike Kelley yelling like Jerry Lewis in the army, and the hypnotic criss-crossings of Straight and Narrow, his films did nothing for me. Conrad did have a few good quotes, though. I wish I had copied them down, but paraphrasing: film is the space between nothing happening and something happening (suitable for a structuralist, I’d say); and later, describing how most artists he knew in New York City during the 1960s didn’t have jobs, or were ideologically against the idea of having jobs: we managed to survive by floating along on society’s economic froth.