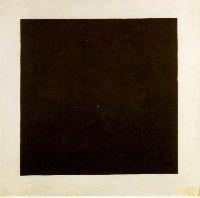

Malevich's

Black Square

About a year ago, I made a brief, wry

comment concerning the immanent demise of both the social-networking site

Friendster.com and the then-popular

flash mob trend. I thought the enthusiasm my friends felt for these phenomena was naïve (“revolutionary” was the word most commonly used to describe both trends), and that, given time, we would throw them into the same embarrassing, slightly campy trash bin now reserved for

Hands Across America and

We Are the World (despite the noble aims of both 80s events – food for the homeless and aid for Africa, respectively – they left a legacy of horrible pop music. Additionally, they traded on the idea of

chic activism: we’re holding hands for the homeless, don’t you want to join? Then you can go back home; help Africa, buy this record. Activism as consumption, see

John Powers: “Take Michael Moore, for example. Back when he made

Bowling for Columbine, one of the weird things was to watch the audience cheer at the end as though they had

done something. All they had done was to choose to go see Michael Moore sort-of do something. That is activism as consumption.”). Once you’re connected to one million people through 85 friends on a network that asks you to list your favorite items of cultural consumption, then what? Once you’ve made silly gestures at the Macy’s shoe department with 100 other clued-in people, then what? Now the

LA Weekly profiles Friendster and flash-mobs together. In

Make New Friends…but beware of Fakesters, Scott Lamb chronicles the fall of Friendster:

I signed up out of curiosity — Dubin was very enthusiastic about the site, but couldn’t really explain what she did with it. At first I did exactly what you’re supposed to do: invite other friends, look for high school classmates, fret over the wording of my profile, and take awkward digital self-portraits in the bathroom mirror. I exchanged messages with people I haven’t spoken to in years, which was both pleasant and awkward. When I ran out of people to look up, I invented profiles for my favorite GI Joe characters (who remain far more popular than I, and have far more interesting profiles).

And then, like a summer fling, it was over. I pretty much stopped using the site after a few months, unsure of what I was supposed to be doing there.

Same here. Exciting: having all your friends (and friends of friends) connected to each other in one virtual space. Frustrating: perpetual potential. It was difficult to find any real use for so many connections. Lamb concludes, “If it’s true that we go online looking for connections that we haven’t made in real life, perhaps the connections themselves can’t bear up under all that weight. Meanings come from relationships, not just connectivity, and Friendster can’t just give you a meaningful relationship.”

Then Alec Hanley Bemis interviews the inventor of flash mobs (“Friendster writ large”) in

My Name is Bill…A Q&A with the anonymous founder of flash mobs. “Bill” sees flash mob predecessors in

Situationism,

Reclaim the Streets,

Chengwin, the Madagascar Society,

S-A-N-T-A-R-C-H-Y,

Spencer Tunick, and

Stanley Milgram. Some of his thought is a bit contradictory (“You didn’t have to feel like you were cool. It got a lot of people to do something that was a little punk, and a little oppositional, just because they thought it was a clever idea and they wanted to see what would happen,” and “The events I did in New York had an undercurrent of poking fun at everyone for being such a herd. Most of them had some dimension of obeisance or self-congratulation…The participants would feel that they were cool just for participating”) but it’s interesting to see how “Bill” re-theorizes the project as it evolves. What started as something “a little oppositional”, a “performance project” and a “prank”, turns into a “compelling idea” about “disrupting the flow of people in a city.”

I’ll be honest. When I started I really saw it as a gag that had an artistic dimension at the end. I expressly tried to make the mobs absurd and apolitical — in part because I wanted them to be fun, in part because I didn’t want anyone to see them as disrespectful of protest, or as parody. What I didn’t expect was how many people would see the mobs as political statements…And the more I did them, the more I realized the mobs actually did have a deeply political value. The nature of public space in America today has changed. It’s shopping malls, large chain stores, that kind of thing. The presumption is that you’re going to purchase something, but once you try to express yourself in any other way, suddenly you’re trespassing…At first, I denied any political interpretations, but eventually I became won over to the political power of my own project.

Elsewhere, Slavoj Zizek describes flash-mobs as protest reduced to minimalism:

Is not the ‘postmodern’ politics of resistance precisely permeated with aesthetic phenomena, from body-piercing and cross-dressing to public spectacles? Does not the curious phenomena of ‘flash mobs’ represent aesthetico-political protest at its purest, reduced to its minimal frame? In flash mobs, people show up at an assigned place at a certain time, perform some brief (and usually trivial or ridiculous) acts, and then disperse again – no wonder flash mobs are described as urban poetry with no real purpose. Are these flash mobs not a kind of ‘Malevich of politics’, the political counterpart to the famous ‘black square on white background’, the act of marking a minimal difference? (Zizek, pg. 124,

Iraq: The Borrowed Kettle)

“Bill” also speaks of the “non-existent” center inherent to flash-mobs: “For example, in the third mob, we lined the banister of this hotel and stared down into the lobby for five minutes. Two hundred people lined this huge, city block-sized balcony, and after five minutes we just applauded. The idea being it was just this crowd of people, but at the center of it was a vacancy.” Doesn’t this image strangely recall the Malevich painting, with the black square as the the non-existent, vacant center of the hotel lobby?

Well, I’m thinking out loud, still sorting out the clues. Question: how does the “non-existent center” relate to Zizek’s “minimal difference”? (Also recall Zizek’s “absent center of political ontology”).